Click here to read 2009 Winners

2010 Writing Contest Winners

The Write Words

Moving stories win annual prizes

(Scroll down to read winners)

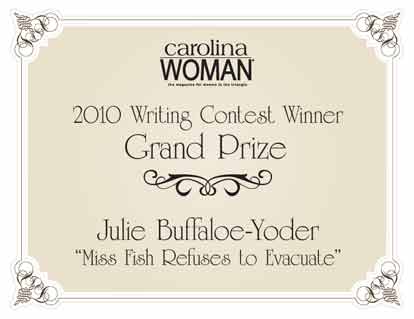

Grand Prize

Four tickets to Broadway Series South's Riverdance performance ($238 value)

Julie Buffaloe-Yoder of Durham, “Miss Fish Refuses to Evacuate”

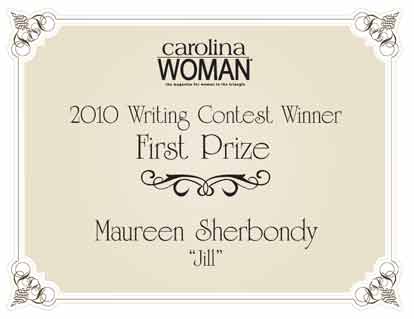

One hour computer repair or tune-up from Tech Wizards ($119 value)

Maureen Sherbondy of Raleigh, “Jill”

One-year membership to North Carolina Writer's Network ($75 value)

Judith Pine Bobe of Raleigh, “Women Buried in Fire”

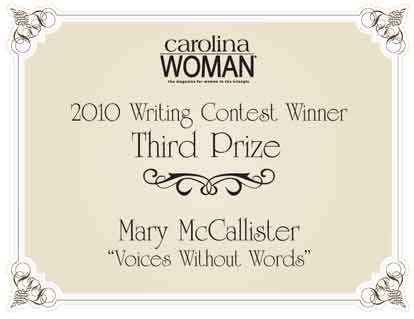

Gift certificate for laptop case and journal from New Horizons Trading Company ($70 value)

Mary McCallister of Durham, “Voices Without Words”

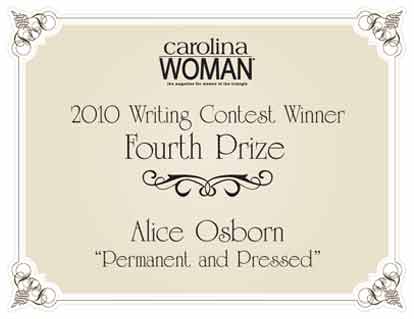

$50 gift certificate to Sono Sushi Restaurant

Alice Osborn of Raleigh, "Permanent and Pressed"

Honorable Mentions

Carolina Woman t-shirt

Jinny Batterson of Cary, "Popcorn Snow"

Madhuri Jarwala of Morrisville, "The Trainee"

Martha Lee Ellis of Raleigh, "Who Are You?”

- Grand Prize

- First Prize

- Second Prize

- Third Prize

- Fourth Prize

- Honorable Mentions

Miss Fish Refuses to Evacuate

Miss Fish Refuses to Evacuateby Julie Buffaloe-Yoder of Durham

Miss Fish sits on the roof. She is seventy-five-years old and hanging onto shingles. The water is now above her windows. It is hot, and the sun threatens to shine. She wears a red bandana as a kerchief. It flaps in the stiff afternoon breeze. Her black boots are muddy. She cut her leg and tore her favorite jeans climbing through the bedroom window and up the old trellis. She dropped her canteen of water. It took too long to get up here. Now all she wants is to be left alone.

She didn’t ask anybody to rescue her. She won’t go. It’s her house. Her land. If she ends up drowning in flood waters, well then. That’s her business. At least she’ll die with North Carolina salt water up her nose.

After the last hurricane, she never saw Almeeta again. Almeeta is her best friend. Now she’s gone. Almeeta’s kids talked her into moving to Chapel Hill with them. Just for a little while until we can clean up, they said. Ha! They sold so fast it made everybody’s head spin. Now Almeeta’s laying in a nursing home, dying with the hard hands of strangers flipping her over twice a day.

Miss Fish is right where she intends to draw her last thin, blue breath. She was born with a rusty bucket in her hand and has worked at McCumber’s Shrimp House since she was old enough to carry it. This creaky yellow house next door to McCumber’s is her home. She grew up here. She falls asleep every night watching the lights of shrimp boats slide across her bedroom walls. She loves the deep gurgle of engines, the shush of shovels in the ice room. She loves the way the fishermen cuss. She loves the smell of marsh mud, the mockingbirds in the trees. Every cypress root and thick patch of moss on this beautiful black ground sings her name.

McCumber’s is on the verge of closing down, but Miss Fish refuses to move. When the developers came and made their big offer, she wouldn’t sell. And now, she won’t move off this roof until the waters go down. Then she will clean it all up, stick by stick.

Miss Fish hears a helicopter again and looks up. It’s the people from the six o’clock ActionNews! team. They will show her on the television tonight. She gives them the finger. She might be an old woman, but she knows what the finger means.

Let people call her a fool. What people say never worried Miss Fish. She gave birth to Cully back when having a baby out of wedlock was unheard of. She refused to quietly leave town. She refused to give him up for adoption. Miss Fish held her head high. She marched to the front row of Oak Shore Baptist Church every Sunday with no husband and little Cully boy in her arms. She made them love Cully. And they did. All the men in the community became his daddy. He had cousins galore. They patted his curly, black head and swung him high in the air. They built him a flat bottom skiff. He spent his childhood in that boat with crab pots and nets. He was a fine, strong boy.

Cully paid them all back by moving upstate. Mr. Big Shot computer programmer. He lives in a fancy mansion in some subdivision that smells like lettuce. He just turned forty, and he acts like an old man. Always talking about how stressed out he is. His prissy little wife acts like she smells dog crap when they visit once a year. And the kids! Two sad, fat boys who don’t even act like boys at all. They sit on the couch all day staring at gadgets in their hands. Whoever heard of an eight-year-old with a cell phone? Kids should be out in boats or playing in the woods.

She wonders what happened, where she went wrong. Miss Fish was the first and only woman in the county to become a captain. She knows currents, wind, and tide like the back of her two big hands. She ought to be taking those kids out on the water and showing them a thing or two. If she hadn’t let Cully sell the boat, she would be on it right now.

Miss Fish was so proud of Cully when he went to college. He was the first one in the family to go. Then he came back and announced that he didn’t want to be a fisherman. Well, that’s his choice. But he could have at least helped her out on some of the campaigns. For years now, she has fought on behalf of the small commercial fisherman. She has protested, written letters, joined groups, gone to meetings. She even goes to the capitol to speak for them. “You just can’t fight it, Mama,” Cully says. “There are too many government regulations. The price of fuel is too high. Too many of the waters are closed. Real estate is the only way to make any money around here anymore. You could sell this place, get a nice condo in town, and never have to worry about finances for the rest of your life.”

A condo! They may as well put her in jail. She won’t do it, not even for Cully. Miss Fish hears an engine in the distance. It might be the Coast Guard. They’ll climb on the roof and carry her off. The muscles in the backs of her legs are knotting up in cramps. She scoots her backside a little to see if she can move. That doesn’t work too well, so she lays down on her stomach and slides toward the chimney. Shingles come loose under her as she moves. She pants. The skin on her arms is on fire.

She makes it to the chimney and catches her breath. The sun has come out now in full force. It is so hot. She wishes she had her canteen. Her tongue has never felt so dry. She wonders how much time has passed. It may have only been minutes, but it feels like hours. Mosquitos swirl around her eyes. Her leg below the knee is bleeding. She takes off her bandana and ties it tight around her leg.

It used to be that the wishes of the elders were respected. When Cap’n Orrie wanted to die on his boat, people let him. Nobody rushed him to the hospital to be hooked up with tubes and machines. His time came, and he left the way he wanted to go—rocking gently in his boat on a soft pile of old nets.

Miss Fish sits up and leans against the chimney. She’ll rest here for a minute and get over this dizzy spell. If she can get a good toe hold of the chimney, she’ll climb inside. They’ll never reach her in there. If they try, she’ll jab their hands with her little pocket knife.

The helicopter circles above her head again. How they would love to see an old fool drown! She sees a boat coming closer. Heat shimmers on the roof. She feels like she might throw up. She looks down at her backyard. Clothes are hanging in the tree limbs. The red and blue patchwork quilt Grandma made looks like a jellyfish flapping in the water. Little white squares float all over the yard. She hopes it’s not the pictures she tried to shove up in the rafters. She sees a patch of green cloth float by. Maybe that’s Cully’s boyscout uniform.

Her little Cully. He was such a sweet boy. He used to peek around the corner of her bedroom to see if she was awake every morning. Then he’d grin with those two front teeth missing. He couldn’t wait to get to the fish house. When he grew up, he couldn’t wait to get away.

It is so hot. So hot. Little white spots jiggle in front of her eyes. The water has leveled off now. If they would just leave her alone, she could

make it. The men on the boat are coming too fast. She can see them now. Their faces are young and round. She hears the beeping of crazy computers inside their boat. A boy talks on a radio and looks bored. Miss Fish gets on her knees and puts her arms around the chimney. She hangs onto the chimney. She stands up.

She never said Cully had to be a fisherman. Even after he came back from college, she didn’t pressure him to go out on the boat with her. He sat in the back room for days at a time. He liked to build computers. He could take an engine apart and put it back together when he was in the tenth grade. It seemed logical that he’d want to work with some kind of machine. She cooked his supper every night and left it covered on a little table by his closed door. She tried to leave him alone.

But Cully could have helped his people with his computers. He could have spread the word. All she wanted him to do was help her make a flyer. She made flyers with an old typewriter. His machines could make fancy colored letters and spit out twenty of them at a time. “This dump is not worth saving!” he screamed. He crumpled up her handmade flyer and moved out that night.

Miss Fish feels faint. Her legs buckle. She tries to hold onto the chimney, but her hands slip. She falls on her side and begins rolling. Sky, roof, sky, roof. It feels like she is rolling into space. Any second now, she will feel the drop. The warm water will clap around her body.

She stops rolling. She is on her stomach again, still on the roof. Her body is perpendicular to the gutter. Her face hangs over the edge. Miss Fish stretches her arms sideways and feels shingles. She digs her fingers underneath the shingles as hard as she can. She should have kept going. If she rocks her body back and forth, she can roll into the water. It will only hurt for a little while.

Miss Fish pants. The sun slaps like a demon against her body. A wild horse floats by, struggling to swim. It is a pretty one, dark brown with a blond mane. It holds its head above the water as far as it can. Its eyes are rolled back and white. Slowly, the head goes under. It comes up again. Then it goes down. The eyes disappear.

There’s a pile of muddy nets wrapped around the trunk of the live oak tree. The net is full of trash and beer cans. There’s the gold lace tablecloth Almeeta gave her. There’s a crab pot buoy. She sees more things from her house float by. But she can’t imagine what they are anymore. Colors appear beneath the surface and turn into a thick, gray line. Everything looks the same.

The men climb up on the roof. In no time, she hears boots thudding toward her. Hard hands grab Miss Fish around the waist. They flip her over on her back. They cut her shirt and favorite jeans from her body. The hands wrap her in a scratchy, wet sheet. Quickly, they carry her down. She refuses to cry.

Jill

Jillby Maureen Sherbondy of Raleigh

I tumbled down the hill alone

really it was a mountain,

there was no Jack beside me,

it was not water at the top

but a wish waiting. I’m not foolish,

everyone knows a bucket set out

in the yard gathers rain. Why climb

a hill for that which comes so easily with patience.

I climbed alone, a star dangled just above

the peak, while reaching for that bright light

I tumbled backwards.

Stardust lingers on my fingers

my back hurts sometimes but

my wishes have all come true.

Jack can get his own damn star.

Women Buried in Fire

Women Buried in Fire

(or the radiation follies)

by Judith Pine Bobé

every afternoon

as the sun hits its stride

trailing shadows eastbound

we gather

homing pigeons into a caged coop

not one of us wants to be here

wearing the same blue dress

fraying white ties dangling from the back

no tea in quaint cups

no scones on flower-patterned china

no marmalade to sweeten the palate

nor the peculiar elegance

of a small bowl of clotted cream

or a transparent cucumber

and watercress sandwich

we hug and talk

in silence only we hear

make idle chit-chat

and big decisions

in a small waiting room

where strangers comfort each other

or cover their faces in magazines

they pretend to read

our party has been crashed

by doctors of all persuasions

professionally smiling nurses

robotic lab techs

radiation gurus

chemo-chemists

never invited

refusing to leave

I worry about

79-year-old Sexy Sadie

a not-so-merry widow

lies about her age

trusts me with the truth

tells me she could still

accommodate my 50-year-old husband

and young Carol

eyes as blue

as a remarkable tropical sky

mother of three Beaver Cleavers

playing Little League everysport

the others

whose names were never exchanged

the lone Black woman

Time Magazine umbrella in one hand

cane in the other

the suburban matron in khaki

a daily headband holding back

straight mouse-brown hair

one by one

we change into civilian clothes

filling them with the scent

of our reddened bodies

we say good-bye

touch a shoulder press a hand

as highways thicken with traffic

and cars cluster like bugs

on a hunt for home

Voices Without Words

Voices Without Wordsby Mary McCallister of Durham

It is estimated that ten percent of the adult population has hearing loss, and that translates in North Carolina alone to 45,000 women. This is one of those invisible disabilities, one that slips from our consciousness even when we know about it. I have learned that “hearing impaired” is a politically incorrect term. For me, the loss has been a life changer, definitely an impairment. While most of us cherish those moments of quiet, those times alone, the real culprit with hearing loss is isolation. My family is understanding and I can afford a hearing aid, but I think of those thousands of women who are alone, and of those for whom the expense of a hearing aid is prohibitive.

Although I have had a hearing loss since early childhood, I was fortunate in many ways. First, that my parents thought that I might become deaf and sent me to an elementary school that had lip reading, and second, that my loss did not become critical until my late sixties. Before penicillin was available to the public, before antibiotics, an ear infection was treated by lancing, cutting the drum so that an infection could drain. The cuts healed, but left scar tissue. In my case, the scar tissue held until the end of my professional life. Ear infections are only one of many causes of hearing loss. I have read that 78 thousand military have returned from Iraq and Afghanistan with hearing loss, and from all conflicts, the number is 750,000. There are so many causes. Noisy occupations, childhood illnesses, head injuries and unexplained birth irregularities are just a few more.

Those who have not experienced a hearing loss may assume that a hearing aid can correct the problem. Sometimes, glasses can correct a vision problem so that vision is as it was before, but that is not the case with a hearing aid, even a really good one. Sounds are not the same; even my own voice is different. Hearing aids allow us to function, but not at a previously held level. They are expensive, up to $6,000, and averaging about $2,000. Medicare does not cover any part of this cost. For many, this is an insurmountable expense. Think of the person who needs two.

I am at an age where many friends are living in senior living situations. One has told me, one who can hear, that she avoids sitting at meals with a gentleman who has a hearing loss, as it makes conversation very difficult, and from one with a hearing loss, that she avoids the dining room for the same reason, difficulty with polite conversation. Most meeting venues cannot afford the equipment necessary to relay the dialog onto a screen, or even for a microphone system. The person who does not hear can only ask so many times without becoming annoying, for the speaker to please speak more slowly, louder, or to repeat something. So, regardless of the passion or the need to know, we simply don’t go. It’s a guess when the grocery clerk asks “paperorplastic?” We answer and hope that’s what was asked. I can hear the words, or some words, of a song that is playing in the background at a restaurant or store, and I remember the song, I can even sing it, but I can’t hear the melody except in my head. It is simply undifferentiated noise.

Like most, I smile a lot to cover my not hearing. It usually works, that is a smile instead of a response. But I have noticed that I am very slow to make new friends. I appear standoffish, and more and more find myself outside of a chatty group, simply because I can’t hear. Granted, the talk is probably inconsequential, even the meeting that I’m missing is mostly the same comment rehashed to the point of tedium. Maybe. Recently, I missed news at a family gathering about the death of an in-law’s brother. I wrote a note the next day when I found out, but felt stupid that I hadn’t heard, and alone.

As part of a report on hearing aids, Consumer Reports (July 2009) found that only 13% of medical examinations include a screening for hearing. This is typical of what I have noticed, the taking for granted of the noises that make up our daily lives, the lack of understanding and importance about how a hearing loss can change a life.

I read, and I know that there are a multitude of instruments to help with hearing. I am ever grateful for the captions that make watching TV possible. I have a hearing aid compatible cell phone and there are hearing aids especially for those for whom music is a priority. But large gatherings, parties and receptions are daunting and I have not heard of any magic that makes them comfortable. I read the stories of the heroes who have not allowed their hearing loss to compromise their lives. I am no hero. I’m an ordinary, elderly woman who is amazed at music without melody, at voices without words.

Permanent and Pressed

Permanent and Pressedby Alice Osborn of Raleigh

On Monday and Tuesday, I’m the churning dryer

that hums and shakes, gathering momentum

for a flush heat to dry even a rolled-up sleeve

tamped down with pebbled soil and bits of bark.

I’m the overloaded closet rod,

crimping and buckling under the weight

of vintage peacoats gray with dust,

torn storage boxes with ugly pink

flowers and the folded

Christmas sweaters with sad bells never worn.

By Wednesday, I’m the runaway

steamroller ironing the long khaki skirt

that can’t stay pressed despite heat, pressure

and patience. Thursday

I’m the wet sock full of sand,

a fuzzy hairbug

that needs to be washed again

although it’s full of Tide smell.

Repeat, rinse, repeat, rinse.

On Friday, I’m a striped silver scarf fraying at the ends,

bunched into a drawer with the others, no peeking,

no Isadora-lengths or silk here. Just 85% cotton

and 13% spandex with a blend of the unknown.

By Saturday, I’m formerly-known as a maroon shirt

with wash stripes down the front and a salad

dressing stain earned last Thanksgiving.

Not all of me

can fit in the washer; there’s always next week

to cycle and sort the load.

Popcorn Snow

Popcorn Snow

by Jinny Batterson of Cary

Saturday morning.

Sister safely aloft on the next leg of her winter off-the-farm vacation.

Larder well-stocked.

Tummy full of pancakes and hot chocolate.

No immediate chores.

A welcome window of time to explore

the whiteness that coated our yards and trees overnight.

Not heavy and dense, like the late January storm and chill

that trapped us indoors for days.

Barely noticeable on roads and sidewalks,

But wrapping itself around branches and bushes and

twigs and leaves and pinecones,

Making miniature moguls so insubstantial they’ll be gone

as soon as the sun comes out.

No need just yet for Olympic vistas of snow-majestic peaks —

Enough to have a morning amble in popcorn snow.

The Trainee

The Trainee

by Madhuri Jarwala of Morrisville

It is the summer of 1981. The air is hot and sticky. My shirt is plastered to my back, drenched in sweat. My hair is coiled up in a bun to have some air on my neck. I am wearing pants and closed toed shoes that are stewing my feet. I am riding in a bumpy, old, rickety, company bus belching black diesel fumes that is taking me to my summer job. I am an engineering intern at a factory near Bombay. The job is to design an electric motor that will meet certain specifications. The bus enters through the gates to the factory’s well manicured grounds. Several buses are disembarking and the worker bees are rushing to the spread out buildings. I get out with the other summer trainees and walk through the factory floor to the design department which is on the top floor in a separate wing.

The machines on the factory floor are roaring. The noise is deafening. There are several assembly lines putting together parts of the rotors and motors. There is a pungent smell of engine oil. The overhead fans are swirling full speed trying to keep the workers cool. They are all men, sweating like pigs but continuing to work without stopping. The floors are dirty with metal filings and dribbles of oil. The air is humid, oppressive. I quickly make my way from this blue collar world to the cool air conditioned world of the engineers and designers.

Ingrid, the secretary, says hello. Her nails are long and red. She has a tight fitting dress, high heels, curled big hair and a bright lipstick. She is typing letters on her Remington typewriter and also answers the phone. She is what is called a Receptionist. Ingrid is the face of the executive suite. She has to be young and decorative. She gets a clothing allowance. She is Anglo-Indian but her skin is quite dark.

Somewhere in her ancestral chain is a British soldier who left behind his name and religion. Ingrid is always nice to me as I am the only woman in the group of college interns. Everybody else is afraid of Ingrid. The rumor goes that she is the favorite of the German General Manager of the plant. He promoted her out of the steno-typists pool and made her his personal assistant. She has his ear and so has special powers over the fate of many. Is it true? I wonder. Ingrid is not married and I have not yet seen the German boss. What is he doing in this humid, sweaty, smelly wasteland of industrial Bombay? Is Ingrid providing him the diversion he needs to make this tour of duty bearable? Ingrid likes my calculator. She says she is always envious of the girls in the professional colleges who can learn all the things men do in the design department. She could only go to the secretarial school to learn typing and shorthand. I go to my desk and immerse myself with my papers, specifications and calculations. Mr. Chandra comes to see if I have any questions. I don’t.

I am startled by the big siren. It is lunch time. We file out of the cool air conditioned office into the blazing sun and walk to the mess where food is being served. The factory workers go to the general area. We go to the dining room which is partitioned away for the designers, engineers and the managers. The area is beautified with a few potted plants of Marigolds and Zinnias. The food is oily and hot; but plentiful. I wonder if the other side eats the same food. There is some time to socialize and smoke if you are a man, before the siren will announce the end of the lunch break.

I talk to Sandip who has just started working here. Sandip is a recent graduate and so our senior. He is appropriately friendly and condescending. He wears a starched white shirt and a tie to mark his position. His dark face is well scrubbed, hair parted neatly and combed with a hint of coconut oil. I bet he knows how to use a slide rule and wonder if he carries a protractor in his pocket. He likes his job. He thinks the factory is good to the engineers. He is encouraging all the summer interns to apply for a job here after graduation. He does not care about the dirt on the factory floor or the lack of air conditioning there. He has not noticed that there are no women in the design department. The most attractive features of the job for him are the free bus ride to work, subsidized lunch, and the three year contract which offers him the job security. Three year contract! I am aghast. Why would you tie your future to this place, fresh out of college? Where is the risk? Where is the excitement? Do I want to be designing electrical motors, ride the rickety old bus, and eat oily food day in and day out for the next three years? There was a loud siren signaling that the lunch time was over. I knew there and then that I was going to do something else in my life.

Who Are You? Living with Alzheimer's — and Surviving

Who Are You? Living with Alzheimer's — and Surviving by Martha Lee Ellis of Raleigh

When your spouse has Alzheimer’s Disease, there are many things you come to know, to expect, to anticipate, among all those things you don’t. Even though you know that some day your spouse may not know who you are, it is a numbingly painful experience when it happens. My husband had not called me by name for some time, but the day he actually asked me who I was sent me into the most painful reaction I had ever had. It was like having ice water thrown in my face: my throat closed up, my breathing stopped as my heart seemed to dip down into my feet. Our relationship flashed through my mind like I was experiencing some terrible accident. I froze.

There was no pretending that this wasn’t happening. No pretending about anything. No matter how well we think we are adapting to living with Alzheimer’s, somewhere inside us for a very long time is the “where there’s life there’s hope” syndrome. That thread unraveled and broke then and there. No more denial.

As I smiled and told him my name, my heart was breaking into a million pieces. And to be honest, at that moment my own mind asked the question “who was he?” In one instant, we had become strangers. Not strangers you reject, in our case. He was still glad to be there with me, but it was grippingly painful for me to be there with him. Who was he? Who was I?

I need to add to this scenario that we were not at home, and the descriptions you have heard and read about the disorientation and confusion that Alzheimer’s patients experience when out of their familiar environment are indeed true. We were actually in the vacation home we had loved for all our married years, and his not knowing who I was continued the entire several days we were there. I spent a lot of time in the bathroom sobbing and just as much time getting myself together to come out.

Returning home did not bring his memory of who I was back, and somehow I knew it wouldn’t. So began a new phase for me of feeling hopeless again. Resilience is a powerful resource that comes to our aid when we most need it, but it took longer to find mine this time.

Eventually I became used to his not knowing who I was, and this was actually because of the way he continued to act pleased to see me. Still, his constantly asking me if I were just visiting, or if I were married, if I had a family, or where did I live, was one of the most difficult adjustments to living with Alzheimer’s I had had to make.

Poignantly, he asked me several times over the next couple of years if I would consider marrying him. It made me feel proud but was no real solace. I still missed him deeply.

Living with Alzheimer’s is the most difficult thing that I think can happen in a marriage. It’s different from the problems caused by alcohol or disease or financial straits or work stress. There is a loneliness that is so palpable you feel as if it is consuming you. You lose your best friend, or at least the person who shares your home and life in whatever way you have built it. I have heard people who are living with a parent or sibling with Alzheimer’s say the same thing spouses experience: (s)he is here but not here.

Surviving the stressful experience is possible, but mostly for those who learn to take care of themselves, to accept help from others, to ask for help from other family members or friends. Finding a support group, as I did, where you can ask questions of people who have been where you are, is the most valuable thing you probably can do. It is there where you find personal answers to your own situations, where you can learn the best way to deal with questions about driving, managing finances, medications, and behaviors. And about your own feelings, which are many, confusing and painful.

The best advice available is “please don’t try to do it alone”. It is truly the most important time in your life to seek support. It may save your life and your sanity.

If you are living with Alzheimer’s, bless you. Surviving it will leave you with an unbelievable dimension in your spirit, your character and your life experience. That’s what you recognize after you have rested and restored your life’s balance, which will take some time to do. But you can do it. I’m here to tell you it’s true.

Unearth Myself

by Anuja Acharya of Raleigh

I could not tell you

Where home is.

I suppose everyone must dig through the dirt of their surroundings

Their distant cousins, their aunties and uncles, their teachers and neighbors

like the insects of last spring, decaying caterpillars and crocuses

to find the precise placement

Of their roots.

I know where my roots are

Entrenched in the gravel, in the soggy rice paddies.

I come from the most magnificent country in the world!

Fragrant with spices, fenugreek and saffron

bursting in bright colors, pink and turquoise like so many tropical fish

With an ancient tradition so unspeakably rich

The undeniable shining diamond in the most priceless crown!

I know where my flowers shall fall

When the petals flutter down with the gust of a breeze.

I am a product of the American Dream!

Here, existence is comfortable, lavish at best

An exceptional part of an exceptional entity that stands

Proudly steadfast in virtues of liberty, equality, prosperity

Literally a mine of opportunity!

These are my roots, securely in India.

Here are my flowers, blooming in America.

But where am I growing? And what does that mean?

I dig through the red clay of North Carolina

I dig through the gravel of Maharashtra

Unearth myself.

A Walk on The Farm Road after Thanksgiving

by Beth Browne of Garner

Sun rust on trees

coin of moon

barest shaving of ivory

off one side

wind hum high

in the pines

shading of sky

mauve to teal

leaf scratching

deep in the woods

circling back

light fading

pines now silent

and the absence of rain

dappled moon

watching over the land

staring wide

marking my course

the cat streaking past

toward home.

Officer Nicholson Arrives Home

by Beth Browne of Garner

Slow crunch of gravel outside

the predawn glow of the window.

A soft tug at the door and he’s home

still swaddled in the stretched-tight safety

of the dark blue uniform.

Peeling away the layers of his twelve-hour shift

he drops exhausted but sleepless

on the cool cotton sheet

which is mussed, but vacant.

The alarm clock bleats unheeded

as, coming and going

they ignore the widening breach

where love clings to a gravelly edge

her grip faltering

as dark birds circle, weightless,

waiting, in case she plummets

to the steep sharp floor

of the bottomless canyon.

Yardwork

by Elizabeth Wallace

The front yard was divided

into squares and triangles

with red tulips in the square and yellow daffodils staged. Crocuses were carefully sidelined to accent the walk.. The pastel hyacinths were quiet in regal standing.

Winter pansies still held forth in their assigned wooden box.

One day he left a note that he wouldn't be back. He signed it simply "your husband".

Later that season a red-violet iris grew

and was soon joined by bearded varieties in dazzling white. They were crowded and could be seen swaying in unison.

Then day lilies opened of tangerine and mango and melon

and late summer roses with robust thorns started to thrive. Butterfly bushes flowered to attract circles of flight

Nests with unknown twineings formed oval dwellings

while a slender wisteria vine grew through the parch lattice

to stay in the floorboards and walls and ceiling of her house.

Lips and Fingertips

by Kristin Kirkland of Raleigh

The warm April sun kisses my skin,

Like the kisses from you

That start between my shoulder blades

And fan out down my arm,

Gliding over my fingertips,

Pausing in the space between.

Love Letters

by Laura Jensen of Pittsboro

They are in the middle drawer of her dresser. It is an old Victorian dresser, wide and long with a large mirror standing guard over a pink marble top. The top and all the drawers are neat and immaculate. The middle drawer is home to her underwear; soft lacy slips, panties and bras in a variety of colors dominated by pink and peach. They are precisely arranged, slips in one pile, another of petticoats, yet another of underpants, then the bras. Not one is out of place. As a child, I remember gazing in wonder at the treasurers in this drawer but never once touched anything although I can’t recall ever been told not to. Touching seemed like an invasion then and it does today.

If I was nearby when she opened the drawer, I could see the stack of envelopes and would have recognized my father’s script. It is hard to guess how many letters there are but so many that she’d wrapped them with a cord, around several times, and then tied a bow. It was string-like cord, white and green in color and, along with the envelopes I can see, look old and slightly discolored.

Now, here I am, holding the stack of envelopes for the first time. Cleaning up after the dead is such a gruesome task. There isn’t anyone else to do it, my father certainly isn’t up to it so it falls to me and it is heart wrenching. Her underwear, let alone the letters, it is all so personal. I stand for some time gazing at the open drawer. I marvel at the fact that it is still so very orderly even in her absence. In her last days she’d probably not worn underwear and I speculate on when she might have last done laundry, by hand of course, and then placed her personal items carefully in this drawer. It smells of her. She only wore one perfume, Germaine Monteil, and all her clothing and everything else she touched has her distinctive smell. I see empty perfume bottles resting in the corners of each drawer, placed there to scent the drawers like sachet. They emphasize the familiar odor.

I kneel down and begin to touch things. I gently rest my hand on top of each pile. I wish they’d disappear so I wouldn’t have to remove them and the task would be finished without me ever having to make a decision as to what would happen to these delicate intimate items. Satin, silk and lace; pale pink, cream, peach, beige and an occasional black item, peak out as the weight of my hand brushes the piles. Tears sting my eyes as memories flood my head. I don’t need to close my eyes to see her in this slip, that bra, those panties. She prided herself on her appearance even at this level, seen only by a few. Although I know she wore these daily, nothing is tattered, no holes or even torn lace, every piece is in flawless condition. It is as if she might reach over my shoulder at any moment and pluck a slip from the pile and put it on. But she will not; not today, not ever again.

I sit down on the floor in front of the drawer and lean against the bed. I wipe my eyes, blow my nose and unwrap the cord from the stack of letters, my fingers shaking slightly. Tucked under the cord is a single sheet of paper folded three times and yellow with age. The letterhead reads:

H. Healy, Jeweler & Silversmith

522 Fulton St.

Brooklyn, NY

It is a handwritten bill of sale dated 12/23/1930 addressed to my father. It describes a “Diamond and platinum fancy solitaire ring, blue white X perfect, weight .42 carat guaranteed. Paid, $165 signed H. Healy.”

I smile. I decide to read her treasured letters and hope the rest of these papers will also bring a smile to my face.

I realize very quickly that here I am, years later, stealing a glance at their unfolding love. By my brief mental calculation, they are nineteen and sixteen when these letters are exchanged. The diamond ring purchased from H. Healy will be presented at Christmas 1930. He will ask and she will say yes. Their wedding will be May 29, 1931. She always said she knew all along she’d marry him; his journals never mention another woman. At her young age dating per se was not permitted particularly in her puritanical family. Many old photos show them together, however, but always with groups of friends. Evidently even then he had a way with words and used his gift to woo her, sometimes from afar.

I open and read the first letter, postmarked Brooklyn August 18, 1927. Dear Little Sweetheart it begins:

“You know dear, I was just about crazy when I got your letter tonight. All the way home in the subway I was hoping and praying there would be one waiting for me. And, when I finally got home (after several years it seemed) there really was one there! Oh, golly Puss, I just tore up the stairs and without even taking off my hat and coat, I devoured your letter.”

He goes on:

“When I got up I went into the parlor and turned on the phonograph. It sounded so nice to hear it I thought. And soon I came to the Merry Widow Waltz you know, and you were sitting over on the sofa so I walked over and held out my pinkie and asked if you cared to dance. And you smiled and said uh huh and took hold of my finger and so we waltzed in and out among the chairs and the sofa; and everything was so nice and your waist felt so nice and soft and delicious like, just as it always is. I could just have danced so forever and you agreed it was nice too. But, the darned record had to run out and I discovered I had only my pajamas on and it was chilly for the window was up and worst of all you were only a pillow! Just when you are enjoying yourself so, all the sweet music stops and cold reality slaps a wet rag in your face.”

He is so in love. I can hardly stand to read his words because it feels like I’m intruding. But, I’m mesmerized. It’s so sweet, so poignant it’s palpable. I read on. In the next paragraph he says,

“Say, you have never kept house all alone for a week. I have eaten all but the wallpaper and we need that. Why do little pigs eat so much? Because they want to make hogs of themselves!”

And then I laugh. I can see his impish grin. It’s the same grin he employed years later to persuade me to eat my peas.

Blizzard Babies

by Lisa Williams Kline of Mooresville

I delivered Caitlin, my first child, via C-section, on a gray January day. When I finally was scheduled to take her home, I woke to see the parking lot outside my hospital room covered in snow so deep the cars were unidentifiable humps, like mattress batting.

“Lisa?” Jeff’s voice on the phone cracked with stress. “Honey, I’m going to try to dig the car out. I’m not optimistic.”

A whole day without him? In my stained nightgown and slippers, I trundled dejectedly down the corridor. I wanted my own bed, my own shower. I wanted to dress Caitlin in the little clothes I had folded so neatly in her new dresser.

As I passed, I glanced into a room two doors down from mine, and saw a guy with an unsettling resemblance to my ex-husband standing next to a bed with a blond woman in it. He was on the phone, and even had a similar insistent, cajoling tone to his voice. “Lydia! You sound fabulous as usual, can you put me through to Jim?”

I took a good look. Good God, it WAS my ex-husband. I dashed past the doorway, instigating a searing pain in my abdomen, then leaned against the wall to catch my breath. I hadn’t seen Reid in almost three years – with no children there had been no reason for contact – and a blast of emotion triggered simultaneous waterfalls of adrenalin, breast milk and cold sweat.

What the hell was he doing here? Did he have a new baby too?

Of course, why should I be surprised to run into Reid in the hospital? After all, Reid was always in the hospital. For some reason, the moment Reid said his vows, he had became an instant hypochondriac. The high-energy marketing major I’d married transformed overnight into a guy who would do anything to get admitted to whatever ward could squeeze him in. Double rooms were better because they provided built-in conversation victims, most of whom were in no shape to run out of the room. Once installed in a narrow bed with its matching narrow closet, Reid would put a shapeless argyle sweater over his cotton gown and pad around the corridors discussing his ailments with anybody he happened to meet.

I limped, dazed, in the direction of the nursery. A rhythmic throbbing began around my incision. Behind the glass window, Caitlin slept, her tiny nearly translucent fingers folded under her chin beneath the edge of the tightly swaddled blanket. After a slight confrontation with a nurse who probably questioned my maternal capabilities with good reason, I retrieved Caitlin and wheeled her by the bundled babies behind the picture window.

I scanned the names printed on the bassinettes. And there it was. “Byer,” the last name that had been mine for four years. Inside, a baby that could have been mine but, by a twist of fate, was not.

Setting my jaw, I headed down the hall, one hand on the bassinette, the other pressed over my now-leaking incision. As I passed, I heard Reid, still on the phone.

“Jim, buddy, I just want to stop in and show you some of the key man plans we can offer.”

I shoved Caitlin’s bassinette, like a cartful of groceries, into my hospital room, skidded in, and slammed the door. I pressed my incision with my palm, which seemed right now to be the only thing preventing my intestines from spilling out onto the floor. I peered over the bassinette’s edge. Caitlin’s eyelids were purplish white, patterned with tiny pink veins.

I shuffled to the mirror. I had on no make-up, and my stomach looked like semi-congealed Jell-O. On the bright side, my hair was thick from the pregnancy, but how careless of me to neglect washing and setting it during labor and delivery. And then there was my stained nightgown, mismatched robe, and grimy slippers.

Stripping down, I turned on the shower. As warm soothing water pummeled my aching sagging body, I reflected that not only had Reid wasted four years of my life, taken our only good car, and Aunt Katherine’s oriental rug, he was now keeping me prisoner in my hospital room with the door closed. And Jeff wasn’t even here, whereas obviously Reid’s new wife, having just given birth, was. He was definitely ahead. If you were keeping score. And, I realized, I was.

Smiling grimly, I rubbed blush on the taut muscles of my cheeks

I had, with idiotic first-time mother optimism, brought a pair of pre-pregnancy black corduroys with me. Just three days ago I’d examined the waistband with hilarity and disbelief. Now I yanked them from my suitcase and tossed them onto the bed like a gauntlet, like a flag before a bull. Dammit, I was wearing those suckers. Just watch me.

I managed to pull the waistband up and over my rear end but with my leaking incision pulling up the zipper was out of the question.

Fortunately, my white maternity sweater now came down to my knees. The phone rang.

“Honey?” Jeff sounded as though he’d just run a 10K. “I can’t get the car out. They’re calling this the blizzard of the century.”

I looked out the window at the glaring white. “Oh.” I heaved what I knew was a very melodramatic and manipulative sigh. As usual, Jeff was being sensible.

Just as we hung up, Sandy, the nurse, bustled in. She plumped my pillows with karate chops. “Ready to try breast-feeding again?”

“OK.”

“If she doesn’t wake up to eat every four hours, you need to wake her up.” Sandy twisted Caitlin’s head and shoved it into my breast as if she were handing off a football. “You need to time each side.” Sandy slid light green liquid resembling anti-freeze within reach, then hurried out.

Caitlin had the most intoxicating smell. Just stroking her miraculously smooth and flawless cheek gave me the most exquisite feeling of well-being. I looked at the clock beside the TV and made a mental note to switch Caitlin to the other breast in ten minutes.

I awoke an hour later with Caitlin asleep at my drained right breast while the left was so turgid it had begun to leak through my sweater. So had my incision. Painfully hoisting myself out of bed, I returned Caitlin to her bassinette.

I saw that Sandy had left the door open and crossed the room to close it.

At that moment Reid stepped into the hall.

Our eyes met for one of those fleeting instants before instinctive social graces kick in.

“Hi!” We both stretched smiles across our faces.

“What an amazing coincidence. “ I smoothed my sweater to make sure it covered my unzipped pants. Maybe he wouldn’t notice the large yellow stain over my left breast or the smaller pink stain below. “I have a baby girl. What about you?”

“A boy,” Reid said. “Laura’s feeding him now. Why don’t I bring them over? Laura would love to meet you.”

Warm colostrum spurted out of my swollen left breast.

“Sounds perfect,” I said. “Give me five minutes.”

I skidded into the bathroom and tried to pump my milk into a baby bottle. After spraying milk on the mirror, the wall, the toilet, and into my own eye, I gave up. There seemed to be no way of telling which way the milk was going. Finally I squirted it into the sink. I’d just finished stuffing a folded piece of toilet paper over the soaked incision bandage when my visitors arrived.

“Hi.” Laura, pushing her baby’s bassinette, had blonde, curly hair, jingly silver earrings, and wore a man’s plaid robe. “What a coincidence, hey?”

“What’s his name?” The baby’s face was still red and, to me, he looked and smelled very unappealing.

“Reid Junior,” Reid boomed. “What else?”

“How much weight did you gain?” Laura settled herself beside Reid on my bed.

I lowered myself into the nursing chair and shifted my weight to one thigh. With both a C-section and an episiotomy, nearly any position was a challenge.

“Laura gained twenty pounds exactly, and she’s already lost all but three pounds,” Reid shouted before I could answer. “Doesn’t she look great?”

“Oh, yes.” So he was keeping score too.

“We went all natural,” Laura announced. “How about you?”

“Oh, the cord was around Caitlin’s neck so I had to have a C-section.”

“Too bad.”

Two points to the plaid team.

“Well, at least her head doesn’t look smushed,” said I, wincing at my own audacity. Two for the unzipped corduroy team.

“Laura’s labor was eighteen hours and a couple of times she was begging for pain meds but she made me promise not to let her have anything so I didn’t.” Reid squeezed his wife’s shoulder with exaggerated affection.

Three pointer.

“Did you know we videotaped Reid Junior’s birth?” Laura said.

“I was right down there with the camera in close-up living color,” Reid chimed in. “Even when Laura was in transition and screaming her fool head off.”

“Goodness,” I said, having completely lost track of the score. Briefly, remembering Reid plodding hospital halls in this shapeless sweater, a lump formed in my throat. I knew, now, why he kept getting sick while we were married, and I was glad he’d found someone to love him.

I wish Jeff had walked in at just that moment, having hailed a passing snowplow, his black hair sparkling with melting snow, his cheeks beet red from the cold. But instead, Laura said “Maybe we’ll run into each other in nursery school orientation,” then pushed her baby’s bassinette out the door. As she passed, I looked down at the baby again. His eyes moved back and forth under his closed, translucent lids, and I wondered what he was watching in there. Then Reid and his family were gone.

“Do you want to meet them?” I said to Jeff the next day when he finally arrived.

“No,” said Jeff. He has never had a desire to revisit the past. “We need to get out of here. It’s supposed to start snowing again. Ready?”

“We just need to put on Caitlin’s snowsuit.”

Her bowed spindly legs reached only an inch or so below the crotch. Her little hands barely reached the suit’s armpits. Jeff leaned over her, his face fatigued, but with an expression of such pure tenderness that I caught my breath.

Sandy, pushing a wheelchair, patted the seat, indicating I was to sit down. “Hospital rules.” I sat. “Now, Dad, why don’t you let Mom carry the baby.”

Jeff was Dad. I was Mom. This was a whole new world.

Working Teen, cir. 1979

by Margie LeMoine of Apex

One summer, I balanced on a barn roof and spread

silver paint on the sheet metal,

scantily clad in a string bikini, suntan oil

and dime store shades.

Late spring, I straddled endless rows of bush beans,

back bent, hands reaching for weeds,

yanking, tossing, and feeling sunburn

on the strip of skin where shirt parted jeans.

Bundled in a pink parka, I hauled a sledgehammer

to the frozen pond and smashed

a hole in the ice for cattle and horses

then dashed to board a steamy school bus.

After high school, traded mortarboard for hardhat,

steel-toe boots and waders, and

knee-deep in foul, brown paper pulp,

I hosed corrugated medium down a factory drain.

At nineteen, I stowed three soft-sided Samsonites

in a Carolina-blue Volkswagen diesel, and drove

five hundred miles with the windows rolled down,

starved for the burden of books.

Social Security

by Maureen A. Sherbondy of Raleigh

Bernice pats the lump of pocketed black pistol for reassurance as she enters Charlotte Savings & Loan – the same bank where she and her ex-husband, Jack, once had an account.

Five years earlier he’d emptied the account of their life savings: one hundred and fifty thousand dollars. She received that darn postcard a month after Jack disappeared with their money. In the hall mirror, fifty-six-year-old Bernice had looked up to see anger flushing her pale skin fuchsia and even her hair grew angry red when she stared at the postcard. A picture of the sun setting over glossy water in Cabo San Lucas. HOLA! in white loopy print mocking her. More like good-bye forever. Adios.She had torn the slick postcard in an angry fit seconds later; her arthritic hands throbbed now just thinking about it.

One hundred and fifty thousand dollars! She repeats the number over and over with each angry step taken toward the teller line. What she could have done with that money! Paid medical bills, prescriptions, a meal out at McDonalds every once in awhile. When her 1982 Honda Civic died, she’d resorted to walking or taking the bus. Little by little her freedom eroded. There were only so many places the bus could transport her, there was no deviation from the set route; and lately she had trouble walking the half-mile journey to the closest bus stop.

Wiping snow from her Goodwill boots, her toes tingle. The boots are half a size too small, but at least they provide protection from the cold; what could she expect for four dollars anyway? She blows onto her swollen hands to warm them.

Jack’s pistol also feels cold. He purchased the pistol ten years earlier, after Bernice was assaulted at the Piggly Wiggly by a robber who absconded with Twinkies, a Dr. Pepper, and two hundred dollars. Bernice had tried to stop him, by grabbing his hoodie, but after he’d regained his footing, he’d pushed her into the pimple-faced bagger and she had fallen, bruising her hip. At fifty-two Bernice had been a strong woman, robust and tall, standing inches over the robber. But it seemed that day in the Piggly Wiggly, the strength flew out of her.

Bernice was no longer angry with the robber or with Jack. Anger was replaced with fear of becoming a street person – a beggar on the streets of her Mint Hill neighborhood. Women from her former book club, docents at the local museum, cashiers from the grocery store would stare at her with pity and then look away.

Pride. Her mother had instilled a sense of pride in Bernice. One day, when her stomach growled for food, Bernice hopped on a bus to the Social Services office. Inside, she stood on line with the pathetic, down-on-their-luck men and women. There she waited, the completed application for assistance wilting in her hands. Then a vision appeared, her mama, who had raised Bernice on her own without the help of a single person or the government. Her mama’s voice echoed Have some pride, Bernie. Bernice’s hand trembled, and she left the line, tossing her application in a trashcan outside.

Bernice was not angry, but she was broke. At the age of sixty-one, wrinkled beyond her years, with no college degree, her only skill was painting. Unframed abstract works of art adorned her apartment walls. She had talent, but not enough to land a gallery show. Bernice had never owned a computer or even sent an email. After Jack abandoned her she scraped by with her job at Jasper’s Family Grocery Store, where she swept and mopped and stocked the shelves. But, two months ago, without notice, when she showed up early for work one Monday morning, an Out of Business sign glared at her from the locked door. There was no severance pay and because she’d been paid under the table, there was no unemployment compensation either.

After fifty job applications in sixty days and no interviews, she’d run out of steam and hope. Her resume was handwritten; maybe that was part of the problem. Her checking account was overdrawn and even the change jar of pennies and nickels was now empty. Yesterday, she’d sat in a booth at the city diner drinking water and stealing small containers of strawberry jam. When the diners at the next booth left behind two uneaten pancakes and half an egg, she’d switched tables, and shamefully eaten the scraps.

The mere thought of living on the street at the height of winter sent shivers up her spine this morning when snowflakes fell outside her apartment window. Bernice hates the cold and had wanted to Florida years ago, but like so many things, that never happened. Why had she never been to Paris to see the Louvre? Or Rome? Was she afraid? The years blurred together in a gray haze, and here she is, still living ten miles from the hospital where she was born.

There are no relatives, except Cousin Mattie in California who sends Christmas cards but has her own problems: breast cancer, a divorce, two alcoholic sons who keep moving back home and crashing her old car. Bernice doesn’t have the heart to ask Mattie for help.

This morning the eviction notice stared at her from the front door, when she locked up, and she had ripped the yellow notice down, then gone back in her studio apartment and cried for hours. Had her neighbors seen the notice, she wondered as she sat in the faded floral chair, staring at the kitchen counter. Then it hit her. Mixed in with late bills on the counter was an unopened white envelope. Ripping it open a statement drifted out of the envelope from the Social Security Administration, telling her that in ten months she’d begin receiving eight-hundred-and-fifty-dollars a month.

“You’re next,” a young man taps her shoulder and nods, pulling her from her daydream and back to the bank.

“May I help you?” asks a perky middle-aged teller who is wearing too much mascara.

The gun feels like an extension of Bernice’s hip, she presses the handle with her shaking left hand. The painful bruise throbs from that robbery ten years ago.

One year in jail would hold her over. Just the other day on the news she heard about a felon who had received a one-year sentence for robbing a local convenience store. She imagines that the prison will be like the one Martha Stewart stayed at in Connecticut. They showed the prison on television – it didn’t look bad, more like a small community college. Martha probably baked for the inmates and made crafts. Maybe the prison officials would allow Bernice to teach painting to the other women. In a place like that perhaps she’d make some new friends, women down on their luck – at least they’d have that common bond.

A warm cell, a bed, a blanket and pillow. She didn’t need much. Some paper and pastels.

Less than one year and Social Security kicks in, one year and a spot might open up on that waiting list for Royal Oak Terrace – that HUD senior citizen facility two towns over. The one with the window boxes of purple flowers in spring, and patios where the residents sit and read and talk. She could spend her time painting those flowers.

The blonde teller is saying something to her. “Ma’m, are you OK?”

Suddenly the face before Bernice is her ex-husband, Jack. Jack with his wiry black hair tinged with grey, his eyes that always appear as if they are squinting, the eyebrows that come together and look like one thick eyebrow. His thin lips are sipping Mai Tais on that beach in Mexico.

Some blonde woman is rubbing lotion on his shoulders. Green bills are sticking out from his bathing suit.

Bernice pulls the gun from her sweatshirt pocket and raises her voice so it is clear and firm. “This is a stick-up.” She pulls a large Ziploc bag from her other pocket and hands it to the perky teller. “Place some twenties in here. Just a few.”

The teller’s hands are jittery, but she does as she’s told. She slides ten twenties in the bag. “This enough?”

“Yes. Now slowly hand me the Baggie.”

Gasps ring out in the bank.

“Are you for real, Ma’m? Don’t I know you? Don’t you have an account here?”

“No questions. Now, press the alarm. Do it now.”

“What? You want me to push the alarm? Why?”

“Just do it.” Bernice looks around for a uniformed guard, but sees only customers fleeing the bank. She takes her Baggie and walks to the corner where the loan officer’s leather seat welcomes her. For a split second Bernice considers taking off, but her aching hip and her arthritic knees would not allow a speedy departure. So, setting the gun on the flat grey carpet Bernice kicks the pistol towards the door, then raises her hands into the air, as if her hands will touch the stars. She waits this way as sirens grow louder and louder in the distance.

by Sarah Simpson of Cary

I’m standing in line to return a Christmas present from my father when I see them there. Just like in the pictures. He is sitting in the child’s seat of the shopping cart and she is gripping the handles of it and making wide-eyed faces so he’ll laugh as their mother hands a receipt to the cashier. Your children. Your wife. Well—ex-wife. I cannot see her face yet and have only seen one photograph of it in which she was wearing dark sunglasses. She was standing between the children as if to claim them as hers alone, one arm around your daughter and another hand reaching down to your son’s chest; he held it, perhaps to keep his balance. Standing up was still relatively new for him then. But now he is three and your daughter is seven. Your wife is forty-two. You are thirty-eight, and I am twenty-five, and we are in love with each other.

It takes me a while to realize that I’m not looking at a photograph. I wait for my heart rate to slow but it doesn’t and I remain disoriented, staring. Your daughter is even prettier in person. In all the pictures she was wearing different expressions; her hair looked mousey brown in some, beachy blond in others. The various angles changed her face completely, as did her smile in this one and her frown in that. But in all of them she had your eyes—blue and heavy-lidded. Maybe her mother has eyes like that, too. I won’t know until she turns around. And when she does, will she have any idea? Will she glance at me and get a feeling?

Your son—you imitate him all the time, slip into his voice without meaning to. On your nights with them I always look forward to what funny quotes you will relay to me. You talk about your daughter first—how she cried when you came to pick them up, and cried again once at your place, and shook her hands in this weird way and said she missed Mommy and wanted to go home even though it had only been a few minutes. You’ve actually taken her home early some nights because you don’t want to force anything. You want to be her ally. Other nights she’s made it through with a phone call to Mom and a project to distract her from what must be the excruciatingly slow passage of time. She sits at your kitchen counter and numbers the blank pages of her notebook, makes lists of anything that comes to her seven-year-old mind, copies down everything you do, every word you say. You wonder if she’s doing this for what she thinks is her mother’s benefit. “Poor thing,” you say, your head drooping. “She’s such a sensitive creature.” And I feel my eyes sting again. You ask if I’m all right. I have a soft spot for father-daughter relationships, but I am not the issue.

Then to lighten the mood you tell me about him: “Little guy was fine. What’d he say tonight?” You’ll look up at the kitchen light to ponder (he says cool instead of school, tote instead of toast, amn’t instead of am not) and while waiting to laugh at your son’s latest I’ll realize that I’m sitting in the same chair your daughter was in just an hour ago. Later, as if reading my mind, you’ll ask if it’s weird for me to be in your house, knowing your kids were just there. You’ll ask if I’m comfortable here. I am. Are you comfortable with me being here? You are. And then you’ll read my mind again. “I wish it could be more…” You’ll lace your fingers in a fist, release them, say, “Some day.”

Yes. Some day. I thought that maybe a year would be adequate time for your kids to accept that you’ve moved on, but it’s already been half a year and I don’t see how another six months will be enough. I’d like to meet them before they grow up too much more, especially the little guy, but if I have to wait three years I will—seems like three years should definitely do it. But you will have to make that call. You’ll decide what’s best for them and I will agree, even if for some reason what’s best for them is what’s worst for me—even if it means I never see you again—I’ll do it, because I love them.

I realized this two months ago while lying with my mother on her bed. We were slightly drunk and glossy-eyed and I was having little revelations, speaking every thought out loud. “I already love his kids,” I said, stunned by the profundity. I don’t fool myself into thinking I even know your kids, but in this case I don’t have to know them to love them—which simply means that I want what’s best for them regardless of how it will affect me. You have unwittingly taught me that this is all love should ever be. It is a liberating paradox, as every truth is in some way or other: love presents us with and simultaneously frees us from ourselves.

I step forward in the line. This area is for returns and exchanges only, and there is a row of four cashiers. Your wife and kids are still at the third one down. There is just one person in front of me, and if your family has not left when my turn comes, my chances of standing right beside them are two out of three. And maybe you wouldn’t think it, but I want to stand beside them. I want to hear your son’s voice. Right now I can only see his little mouth moving but he seems to be talking to himself, maybe just loud enough for his sister to hear. She is still holding onto the shopping cart handles, leaning back and looking up and letting her mouth hang open. Her blond hair hangs down from the back of her head in tangled waves. My hair looked just like that when I was her age, only dark brown. I find myself wishing for seven years old again and your daughter as my best friend. Your son looks up at the ceiling with her but cannot see whatever she sees as she swings her head back and forth.

The man in front of me must have forgotten something because he steps out of line and heads for the exit doors in a huff. I move forward. There is now nothing but air—perhaps fifteen feet of it—between me and your family. I could speak your children’s names and they would hear me. We could make eye contact. I could smile at them. Give them hugs and smell their hair and kiss your son’s sticky cheek. I could tell your daughter that everything is going to be all right and that she needn’t take on the worries of her parents or any adult. She needn’t feel guilty—and I’m not talking about the way people say kids blame themselves for their parents’ divorce. I’m talking about guilt for leaving Mom twice a week to have dinner with Dad. Guilt for not wanting to be with Dad even though she knows (she must know) he loves her. Guilt for crying all the time and not knowing exactly why, which reddens Dad’s eyes with patient concern, which makes her cry even more because he is so patient. But your daughter doesn’t know me and even if she did, you’ve told her all these things again and again in your sincerest of voices. Children just don’t understand how true it is, how many lives we get and how many different kinds of okay there really are.

Your wife shoves an item I cannot see into a white plastic bag and then throws the bag into her cart. I still haven’t seen her face. The cashier’s face is flushed; his eyes strive for apology but don’t quite make it—there is just a hint of smugness, and something close to relief as he watches your wife gather her purse. She is tall (I knew this), thin (she teaches yoga part-time), and her skin is probably tan in summer but is now faded to fair. You must’ve made a handsome couple. A perfect little family, on the outside. I notice her thin wrists and long, slender fingers as she puts a hand on your daughter’s head. I want to see her face, and just as I’m about to glimpse her profile she pulls the sunglasses back over her eyes.

I hear the cashier saying Next person—Ma’am?—Miss? as your family walks away, as your wife lifts your son from the shopping cart and lets him stand beside your daughter, who tickles his belly and says something to which he responds, “No, I amn’t!”

Loud and clear. I am suddenly breathless. I step aside in the line and the person behind me goes ahead without seeming to notice my distress. I watch them recede through the blur of what must be tears, but your kids are hardly real now, because I do not exist. I may as well be a photograph they’ve never seen.