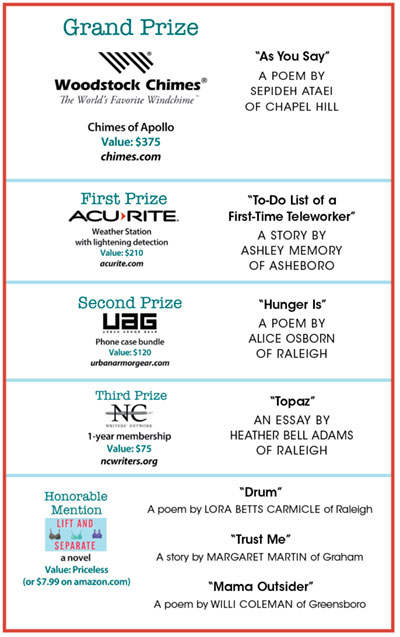

Power of the Pen

Winners of our annual writing contest

"Thanks for inspiring readers to become writers," said a Chapel Hill resident in a note with her short-story entry in the 2017 Carolina Woman Writing Contest. It's a mutual admiration society! Thanks to all of you for submitting your work. Congratulations to everyone - from newbies to prize-winning scribes - who sent in fiction, nonfiction and poetry. In my opinion, just keeping your pen moving makes you a champion.

– Debra Simon, Editor & Publisher

"As You Say"

by Sepideh Ataei of Chapel Hill

Amber tea

swimming

with leaves,

fragrant steam

bedewing

my nose –

tea-cup stratified in tawny, ocher and ochre.

I've forgotten the first –

undoubtedly

placed in my hands

filled

to the brim with demand,

served

in virgin-white porcelain,

sipped

through resignation,

eyes soaking up steam,

leaves

stuck between teeth

bared in a wide smile –

as you should.

The air smells of pita bread

smothered

in feta cheese–

bites slowly

roll

down my throat,

tea grows tepid –

quickly, don't you have work to do?

Sundays are for studying –

tests

consume

my glory days,

frequent as they are –

nothing worth it comes easy, dear.

Readings for English –

unimportant,

focus

on

the

future –

you will make a great doctor.

Hair

flows down my back,

a straight

waterfall –

satiny and pristine,

born from a super-compressed

mane

of knotted curls,

always

placidly floating.

Brides have smooth tresses,

zereshk-stained lips,

sun-lit golden eyes

twirling hands –

happy,

as you will be.

His gaze

flickers

to the sound of applause,

an ocean wave

undulating

for the moon –

our eyes meet:

his ever-widening smile

distracts

from his blank eyes –

what a nice grin he has,

so handsome,

yes?

Bone-white walls

scattered

with empty frames,

awaiting

child-filled memories –

furniture flawless,

smelling

of antiseptic money and artisans –

you are both doctors, after all.

The lone purple pillow,

afloat

on the wide ocean that is our bed

constitutes one

dash

of color in the house –

you insisted.

In autumn,

trees blaze,

leaves gliding like a

snowstorm of wildfire set alight in rainstorms –

sunlit opaque windows

smear

mosaics everywhere,

distorting reality,

bathing

me in kaleidoscopes of illusions –

close it, it's dangerous!

Nature

is

beloved

by all Iranians –

the bubbling of a brook,

cheerfully chirping songbirds,

gales that coax hair into dancing,

redolent plants permeating the air

tingling our nostrils –

such life gives liveliness, no?

Naturally,

family picnics are a must –

the kids adore

these

picturesque events –

look, all your walls are finally covered.

Their births

exhausted,

as did conception –

a perfectly matching set,

one carved out of us each

but

inseparable:

a peculiar blessing –

proof you're meant to be.

First beholding them,

so reminiscent of ET,

my fingers relentlessly

prodded

the squealing mess of their faces,

whip-cream soft

just as pure,

layered –

vision hazy,

like the movie,

I wept from instant irrational love

sodden

with sadness:

I don't want to see them go –

has he seen the little angels yet?

My Melody,

his Rose –

both all mine

for a time–

aren't they worth it all?

Life is decisions.

I've made mine,

not freely,

but I'm no untouched island:

whispering

waves

commanded

me

daily –

depart now, daughter.

"To-Do List of a First-Time Teleworker"

by Ashley Memory of Asheboro

Teleworkers need to be careful they do not slip into "workaholism." They should give careful consideration to the balance of their work and personal lives to avoid burnout. – U.S. Office of Personnel Management

7:30 a.m. - Get up and throw on an old T-shirt from the dirty laundry. Gloat over the fact that you will be uberproductive while your co-workers are trapped in gridlock. Scribble your to-do list:

- Respond to a call from Suzy Costas, a reporter from the Herald Tribune

- Draft remarks for your boss Cynthia, for a reception celebrating the transit system's anniversary

- RSVP to the office picnic

- Write a poem about the baby bluebirds learning to fly in your backyard

- Spend some time playing with your dog Buster, who's been feeling neglected

- Make a grocery list for the weekend

- Wash all of your dirty dishes by hand because your dishwasher leaves spots on your glasses

9:00 a.m. - Realize that your back hurts because the chair you're sitting in is not ergonomic. Review the office policy to see if a new work chair for home is a reimbursable expense. It is. Spend a long time going through the online inventory of office chairs at Staples. Rule those out because they are ugly. Look instead at the Ikea website because if your work station is at your dining room table, your new chair ought to match the others. Call the 800 number and order swatches since the online images may not be true to color.

10:35 a.m. - Open email from Bryce, an employee you manage, asking you to proofread a brochure. In the same email he asks you to call Suzy Costas because she's called a second time. Suddenly remember that you did not eat breakfast. You usually order this from a drive-through and eat it on your way to work. Decide to make yourself an egg sandwich. Realize that you do not have eggs.

11:05 a.m. - Arrive at the drive-through. Be told that you are too late for breakfast. Throw a fit because you're a regular customer. The manager comes to the window and says something about their standards and how older items are cleared by now because they would have deteriorated in quality. Resist the urge to get out of the car and go inside and ask the manager since when has the word "quality" been synonymous with fast food because you are not wearing a bra.

11:30 a.m. - Return home and decide to wait until lunch to eat. Try to entice Buster into a game of catch but then realize he's not interested in interrupting his nap on the sofa just because you happen to be home. Decide that at least one of you should get some exercise.

11:40 a.m. - Get on the treadmill. Watch HGTV while you exercise. Feel badly because modest updates to your décor can be done in just half an hour and you haven't even removed last year's holiday wreath. Order a pizza.

12:15 p.m. - Answer door. Realize that you are lonely and that the pizza deliveryman looks like Joseph Gordon-Levitt. Try to interest him in going out with your sister. Realize that he thinks you're the one who wants to go out with him and he isn't interested. Binge-eat for the next 20 minutes.

1:15 a.m. - Decide that you should get caught up on the news and make sure nothing cataclysmic has happened today. It has. But instead of reading about an earthquake in remote parts of China, watch a video of a bulldog on a swing. Then get absorbed by a love letter from Arthur Miller to Marilyn Monroe now up for auction at Sotheby's. Examine your own derriere. Would it remind anyone of sweet cantaloupes? It would not.

3 p.m. - Check email again. See message from Bryce asking why you haven't responded about the brochure. Make a note to have a meeting with him soon to discuss his tone. See another email from Cynthia titled "Call Suzy Costas!!! Where is my speech???" Make a note to explain later that her browbeating is interfering with your productivity.

3:10 p.m. - Try to RSVP to the online invitation to the office picnic but stop when you realize that all of the good bitmojis have been used. Give up and go on Facebook. Learn that Camille Townsend, the girl you hated through high school, just updated her status with news of a promotion at work that will require European travel with her new Italian boyfriend. Hate her for another 10 minutes. Find a picture that makes her look fat.

Feel better. Troll the internet for a less stressful job that doesn't infringe on your personal life.

4:35 p.m. - Look back at your to-do list and decide that most of those things can wait. Sit in front of the window and start poem. Realize that while you've been working, all the baby blue birds have successfully flown from their nest. Understand that this is what happens when you become a workaholic. Decide to take tomorrow off. Start the dishwasher.

"Hunger Is"

by Alice Osborn of Raleigh

a plastic bag in May

waltzing across bare parking lots.

The neighborhood's tarred up telephone poles

drenched in sepia and creosote

trap famished flies.

Can hunger be strength;

a willful dance

of power, denial, refusal?

Stop your whining

and do your writing instead

of distracting yourself

with cheese sticks and lightly salted peanuts!

Eat and eat. Never be satisfied.

If you don't eat?

You won't die–this isn't The Grapes of Wrath.

You need courage not to give

into buying more Amazon T-shirts,

sustainable striped scarves,

more cookbooks for all the uses

of buttermilk. But yes to more drinking books

about the history of whiskey–

how does the angels' share

evaporate more drops in Kentucky than Scotland?

Another hour lost to heavy alcohol study.

Hunger locks you into the future,

but also the past. Can't leave

this place of neither up or down.

Meditate? Contemplate?

Without attention you'll wither

like those angry grapes. Or starving insects.

You don't want to eat silence.

You want bacon. Fried, please, with the crispy

ends covered in pimiento cheese.

You know, the homemade kind.

"Topaz"

by Heather Bell Adams of Raleigh

When we were growing up, our parents often took me and my little sister, Melissa, to the Henderson County Gem and Mineral Show, part of the North Carolina Apple Festival held over Labor Day weekend.

Over time, the show has been held in different locations, but the basic premise is the same–to show off the ruby, diamond, agate, amethyst, quartz, topaz, sapphire, emerald, garnet, peridot, moonstone, citrine, opal, and tourmaline gemstones mined from the green hills around us, in places like Franklin, Spruce Pine, Cowee Valley, and Hiddenite. Vibrantly-colored stones born from the earth's constant shifting, the increase of pressure, and the application of heat.

It must have been at the show where Melissa and I learned that the nation's first gold discovery was at Reed Gold Mine near Concord. We heard about how our state is the only one where the "big four"–diamonds, emeralds, sapphires, and rubies–have all been found. That the beauty of emeralds comes from something broken, the beryl and chromium merging together in six-sided prisms within pockets of quartz veins formed only after the bedrock has cracked. That underneath the ground where we lived on Kanuga Road, halfway between the antique stores of Main Street and the low rock walls of summer camps, there might be something more than dirt, something valuable.

We lived ordinary lives in that white house on Kanuga Road, the one with a concrete sidewalk that looped around the yard, perfect for riding bikes. Ordinary until it wasn't. Our mother, who was almost always in motion–organizing closets, soaking the labels off used peanut butter jars, stretching up to dust the books on the top shelf–one day couldn't get out of bed.

Here we are–I'm sixteen years old and Melissa is fourteen and we're waiting on our grandparents' scratchy couch. When our dad gets back from the hospital, the TV is on, but only for the sound, which fails to drown out the words he has to say. Cancer. Leukemia. Words that, if they had a color, wouldn't be anything but brown.

A year later, when I knock on her bedroom door early one morning, Melissa is already awake, standing by her bed and holding onto the bedpost like it will keep her from falling. I'm the one who has to say the words this time. Our mother is gone. I don't say she'll be buried in the same ground that has turned up rubies and emeralds because I don't think of it, at least not then.

I can still see my sister that morning, young and scared and standing very still. On the shelf behind her is a brown paper bag, a "grab bag" from the Gem and Mineral Show, the same kind of bag our mother used to pack ham sandwiches for our school lunches. Sometimes in those grab bags you'd get smoky quartz or a tiny amethyst, always at least some flakes of mica or chips of garnet, something to assure you that your money wasn't wasted. That day neither of us touch the bag on her shelf, which is crumpled and tipped over on one side, because gemstones and anything sparkly are far from our minds. Melissa has already opened the bag anyway. She has already decided it's worth keeping.

When I leave for college a few months later, Melissa and our dad live together in the house on Kanuga Road, together and yet each alone, a time which forges a bond between them much deeper than the stories imply–the head-shaking over a thermos of hot chocolate that exploded in the kitchen, the grimacing laughter about the frozen dinners they ate and the women from the church choir vying for a date with our dad.

How does loss take its toll? How much might be enough to hollow out what was once whole?

This is my sister at college–laughing with her best friend, Molly, cooking in a tiny toaster oven stacked on top of a dorm-sized refrigerator, trying to mediate a dispute among her suitemates. And–because she's a person and not a saint–banging her notebook down on her desk, frustrated with the foreign language requirement. But mostly laughing with Molly.

And here she is a few years later, hearing that a tractor-trailer struck Molly's Honda Accord, that it barreled down an embankment, that Molly was killed. So here is Melissa, an expert now on letting go, this time robbed of the opportunity to even say goodbye.

To be fair, we have a father who would do anything in the world for us, good health, good jobs, grandparents, aunts, teachers, and friends. And now a kind and generous stepmother and husbands and sons of our own–gifts that are whole and pure, that fill us up.

Yet even without all that, at her core Melissa has always been more sweet than bitter, more light than dark. She makes the four-and-a-half hour trip across the state to attend my son's first birthday party even though back home she has a long to-do list and a ten-month old of her own. She sends mail–anniversary cards and "just because" cards and magazine pages of dresses and furniture she thinks I might like.

This sister of mine makes spaghetti sauce from scratch and knows the best way to serve tacos to a group. She sends me recipes–lots of different ideas for chicken because she remembers I don't like red meat.

Recently, I was thinking about how much and how well she cooks because I cook only enough to get by. I told my husband, "Well, you know, I didn't really have the chance to learn how to cook from my mom." And then I thought of Melissa, who has a cupcake holder and a cake stand and insulated devices to keep casserole dishes warm during transport. Who was either paying better attention than I was or has since taught herself.

This is who she is now, when we return as thirty-something adults to the Gem and Mineral Show, taking turns pushing her younger son in his stroller and reminding the older boys not to bump into the trays of gemstones on the folding tables. This is her smiling at the man selling citrines the color of sunshine. She buys a citrine ring as we remember that the yellow topaz was our mother's birthstone, more gold and less sun, but a similar color. Topaz, from Topazos, the ancient name of St. John's Island in the Red Sea, which was difficult to find and from which a yellow stone was mined, or alternatively, from a Sanskrit word meaning heat or fire. Known chemically as aluminum silicate fluoride hydroxide, topaz is, because of its strong chemical bonds, the hardest of silicate minerals. In ancient lore, it cured fevers and was said to have the power to cool boiling water as well as excessive anger.

As we leave the show, Melissa reminds me of the blue topaz ring she often wears. Although topaz comes in multiple colors, the blue is rare, made by what so-called experts deem impurities in the stone.

"Right, you've always liked blue," I say, assuming she's casually cataloguing the jewelry she has picked out at the show over the years.

"I got it–the blue topaz one–with Molly," Melissa says. Her voice cracks the slightest amount. "We picked out rings that looked alike."

"I didn't remember that," I admit. I should have remembered.

But she smooths over my mistake because this is who she is. Bright, saturated colors where there might have been only sadness, the color of dust. Maybe this is what constant shifting, the increase of pressure, and the application of heat do to some people, when the conditions are right, when there lies underneath something crystalline and extraordinary.

Honorable Mentions

by Margaret Martin of Graham

When I tried I remembered, slowly but clearly, when I was a boy, how my mother taught me to love. Louis Santter was my name. I was thin in the way that those who worry can be, strong in the way that those who know success can be, and afraid in the way that those who have forgotten can be. I was uncertain, hungry, eager to draw solid lines on any surface. At that time, I did not think about past or future. I only felt my fingers itching to draw trestles, bridges, archways, and intricate spiderworks of lines to bear up under pressure.

I lived in a village called Feldkirch with my mother, who seemed already old when I was born, and my sister, Claire. We had no father. Though Claire was almost old enough to be my mother, she had no maternal leanings. She seemed curiously uninterested in what went on around the house. She liked the feel of well-worn cloth, and she wore shapeless light-colored dresses over her dark wool. I cared nothing about clothing except in the intense cold. I would have worn nothing to feel the air enter and leave my pores like water.

Then, I had a thick shock of dark hair, and wide, unblinking eyes. My hands were large, my slender fingers white, breakable. My sleeves were too short. I did not like school. When I spoke my classmates looked at me blankly, then poked each other, laughing. Only one boy remained silent, looking at me then at the floor, maybe hearing, like I was, the noises in the room flying around like trapped birds.

Then, I had a thick shock of dark hair, and wide, unblinking eyes. My hands were large, my slender fingers white, breakable. My sleeves were too short. I did not like school. When I spoke my classmates looked at me blankly, then poked each other, laughing. Only one boy remained silent, looking at me then at the floor, maybe hearing, like I was, the noises in the room flying around like trapped birds.

Mrs. Sonjardt, our teacher, was young, and lovely.

Will you read to us, Louis, she asked, kindly, when we met in our classroom morning after morning.

The other children waited too.

Mrs. Sonjardt repeated, Will you read, Louis?

I watched the wood grain in my desk until I saw the dark lines and grooves giving way to waves which revealed the amber hues beneath. I stared until it became a wolf, with thick coarse fur and shining eyes, breathing its sudden life into the air I shared. How could I answer when this hungry wolf waited?

No matter, said Mrs. Sonjardt. Maybe tomorrow.

Everything I looked at long enough changed shapes to show me how unstable matter is. Everything always changes, quickly, when you can see it. I stared at the red hat and mittens of the girl who sat beside me, at her pink hands, the curls which dangled behind her ears. All of it merged into a watercolor muddle with an ice blue layering on top so I could hardly recognize this girl who sat just a few feet from me for repetitious days.

She became lost under this ice blue layer, as if her life were trapped beneath the dark river's crust. Her cries were silent. I could only watch and wonder, because when I saw her face at the desk near mine, I saw laughter, bright eyes, and an impossibly steady hand holding her yellow pencil.

I had to learn to know the world. I studied the old trees and how sinking roots into the ground kept them upright, even in most storms. I pulled loose threads from my wool sweater, wondering about their color, how it was made, what made it a thing worn by a boy. How old was I? Why did the number mean so much to those I passed running up the trail to the village? I felt ageless and misplaced. Sometimes I could not think clearly enough to cook porridge for my mother when she rested. Once I lost myself while the water boiled and the pot was scalded black. I was gone into a traveling song with a swan, which drew me to it in my dreams. The long neck and black-masked beak, the bowed head, the odd loud sound surprised me. The drifting through water so peacefully. Then I smelled the smoke and remembered the water boiling. My mother shook her head but did not scold, because she knew it was of no use. My sister ridiculed me and did not hide her disgust. I felt useless before her, even though I saw within her a gentle spirit waiting for her anger to turn to something graceful.

How could I speak the thoughts which fell like raindrops, snowflakes, flecks of dust through light. I tasted them as though they were gold, real as the petals on the flowers my mother and I saw on our morning walks. I carried charcoal to draw the swirling lines which came to me when I raced to the edge of the mountain slope and looked out into the bright sky to touch the clouds. Once I was afraid that I would fall from the edge because I had suddenly lost the taste of the heavy clouds which held rain. I bent and drew the way rain had felt to me, the stained glass of stars which I saw in their glittering glory, the tears of angels falling. When I followed the path home, for a while I was sad for what I had lost.

My mind was crowded with pictures. I heard people speak, even my sister in her sharp tones, and I heard the words in colors, brassy echoes which rang until my head hurt. I wanted to plunge my head into the cold water until the sounds became strings.

As I became a man I grew a beard that I could see and stroke to show me that I was not lost in time, that I was aging and growing and moving, as people do. My thoughts whirled, dusty and glowing, then ducking into ice blue, with the image of my young schoolmate and her dangling curls trapped beneath the river crust, banging and begging to be heard. Then a star burst, like the burst of seeds from a flower and the faint wisps of dandelion threads left over.

Where do the seeds go?

Don't worry, Louis. My mother said to me, gently. They will know where to go.

She watched me closely when we were together, with some worry and total love.She served us supper on familiar plates, the smell of chicken with cabbage and garlic rising from them, and we broke our bread and ate in full silence.

Claire moved away to marry a gruff man who spoke in tones which matched her own. He had square hands and wore stiff shirts. Our mother got sick with fever one day and never arose again. She lay beneath the blankets as the color came and went from her cheeks. I heard the sorrow in her breath. She grieved for me, she said. I did not know how to help her. I sat close and sang about sparrows, swallows, robins, about eggs and mothers who warmed them. I sang about all I saw from the treetops, the twigs entwined, the dry, warm straw.

Will Claire be happy? I asked one morning. Mother looked at me then turned away.

I don't know, she replied. I hope so.

Will you? She asked. Be happy?

Yes! I said, holding her hands. Thanks to you.

I remembered Claire's face and pretty hands, her blue eyes so rich in deeply buried dreams. I imagined her laughter. I imagined a father for us, a man with a hearty laugh who loved to eat, drink and back-slap his boisterous friends. He was broad, bearded and wore spectacles which gleamed in the light, as did his bright gold wedding band. His love was a ring of fire and ice, a trust in life's roaring colors which waved and rippled, bouncing from walls and tabletops through doorways and windows of every house.

In an early morning mother died.

Where are you? I asked into the air.

There is no empty space; I am here.

Then I heard birds sing and wolves howl. I saw fish jump. I saw myself as the bird, the wolf and the fish, and I felt my own timber crash inside as loud and heavy as an ocean wave. I felt all, even while I watched myself tremble, a child again. I whirled in her compassion for me and humanity, and I made my memory of her happy times, her patient smile, her peaceful joy. I felt her pain leaving as she whispered, I love you. I remembered how love echoes in every heart's chambers.

Don't be afraid of love.

Love seeped from so deep that there was peace like the blue sky, the trickling stream, and no in between. My mother whispered truth to me through space and time, shattering every fear in the bright feathery shine of wings.

Trust me, she said.

I gave you life to enjoy.

I will, I said.

I do.

I love you.

by Lora Betts Carmicle of Raleigh

The drum maker handed the instrument to me.

She said

It is yours

Play!

Feel the beat, find your rhythm, follow your heart.

You can play your way

fast, slow, soft, loud

change the rhythm whenever you choose.

As you play your songs

others will be astonished at what they hear.

Some will try to join in, but

your rhythms are different, so complex.

You will have to teach them to play.

They have instruments, too

drums tucked away in their secret places

safe, protected, but

unused for so long.

They will watch your hands and listen;

Their hearts will move their hands in rhythm.

They play!

Finally, making the music of life.

Some cannot find their instruments, so

their bodies sway in time

their feet move to the beat–

drumming

creating the dance of their own choosing

fast, slow, softer, louder,

first simple, then complex

everyone improvising

finding the beat, the pattern, the rhythm

that blends into a new song.

by Willi Coleman of Greensboro

Today

I am decades

past the age

my mother was

when she delivered me

into this place

Born in 1920

just months before some

women were given the vote

Mama was aware that

even after birth

women like her

had to just get up

shut up and suit-up

for one more battle

But still

She panted me into

the world in a city

that another wet, wild

and roaring woman

they named 'Miss Katrina'

would try her best to just about blow

off the map

Now, knowing the price that was paid

as I swept into town

I try to live my life well

But with each passing year

I wonder anew

how women like my mama

without

the comfort of money

the safety of acceptance

the protection of power

somehow managed

to wash pride into baby bones

to push strength into childish spines

to bleed enough love to last me a

lifetime